This past Saturday was the second annual Current Research in Digital History conference, organized by Stephen Robertson and Lincoln Mullen (with help from the amazing Thanh Nguyen), and co-sponsored by Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, the Colored Conventions Project, and the African American Intellectual History Society.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with CRDH, it’s an annual, open-access and peer-reviewed publication with an associated conference – more information can be found on its website including past volumes of the publication, past conference programs, and (eventually) the new CFP for CRDH 2020. You should definitely come to CRDH 2020. And bring a friend!

As an inveterate conference tweeter, I spent a lot of time on Tweetdeck during the conference and was generally pleased by the amount of Twitter engagement we had given the small conference size. So in honor of the conference Twitterati (is that a word? It is now!) I’ve done a quick analysis and visualization of our activity.

Global Network Stats:

Nodes: 198 (people with separate Twitter @-handles)

Edges: 552 (tweets and retweets)

Average weighted node degree: 4.369 (@-handles were mentioned in an average of 4.369 tweets/retweets, including repeat mentions)

The network is disconnected (there are people who used the hashtag who never tweeted to each other or retweeted each other’s tweets) into two components and the largest connected component has diameter 5.

The Major Nodes:

When looking at the conference network, some nodes immediately jump out due to the node color/size scheme I’ve applied to the visualization: nodes with lower degree (less tweets originated with or included that @-handle) are blue while nodes with higher degree (more tweets originated with or included that @-handle) are yellow, orange, or red and progressively larger as we get towards the red/highest (unweighted) degree nodes.

If we look strictly at the numbers, the top nodes by (weighted) degree are jotis13 (yes, I’m writing about myself in the third person); jimccasey1; nolauren; JenServenti; CCP_org; profgabrielle; dgburgher; chnm; historying; seth_denbo; FreeBlack TX; and harmonybench. This is not, strictly speaking, surprising as these were heavy conference tweeters and/or presenters who included on their Twitter handles on slides for easy tweeting of their research.

However, if we look at betweenness centrality (which is another network analysis metric that measures, if you’re trying to get from one part of the network to another as efficiently as possible using the edges, which nodes do you go through?) we get both some familiar orange/red nodes as well as some of the yellow, middling-degree nodes: jotis13; JenServenti; jimccasey1; nolauren; seth_denbo; historying; CCP_org; profgabrielle; Zoe_LeBlanc; kramermj; and harmonybench.

The contrast between these two measures enables us to draw some conclusions about how different Twitter handles were functioning in the network. For example, both JenServenti and seth_denbo rank significantly higher in betweenness centrality than node degree; their importance as connectors in the network were higher than expected given their volume of tweets/mentions. Given their respective positions at the NEH and AHA, the fact that they’re also essential connectors in this Twitter network should perhaps not be surprising.

By contrast, CCP_org and profgabrielle rank higher in node degree than betweenness centrality. A quick sneak peek at a different network measure – closeness centrality, basically how central a node is to a network – shows that they are tied for the second highest closeness centrality in the network (after jotis13). So while CCP_org and profgabrielle may not be on as many of the shortest path through the networks (likely because those paths are routing through jotis13 instead) they are two of the three most central nodes in the network. In other words, their voices were vital to the conversations we were having (both in person and online).

Another particularly interesting thing to note about nodes with high betweenness centrality is that neither Zoe_LeBlanc nor kramermj were physically present at #crdh2019. While this is not an unfamiliar phenomenon – conference tweeting, by its very nature, enables the virtual inclusion of people at conferences – what is particularly fascinating is that both of them played a very similar role in the network. Specifically, they signal-boosted a conversation about the diversity of digital scholarship to a wide variety of people who were not present at #crdh2019 and didn’t necessarily participate in wider conference conversations.

The Viral(ish) Subtopic:

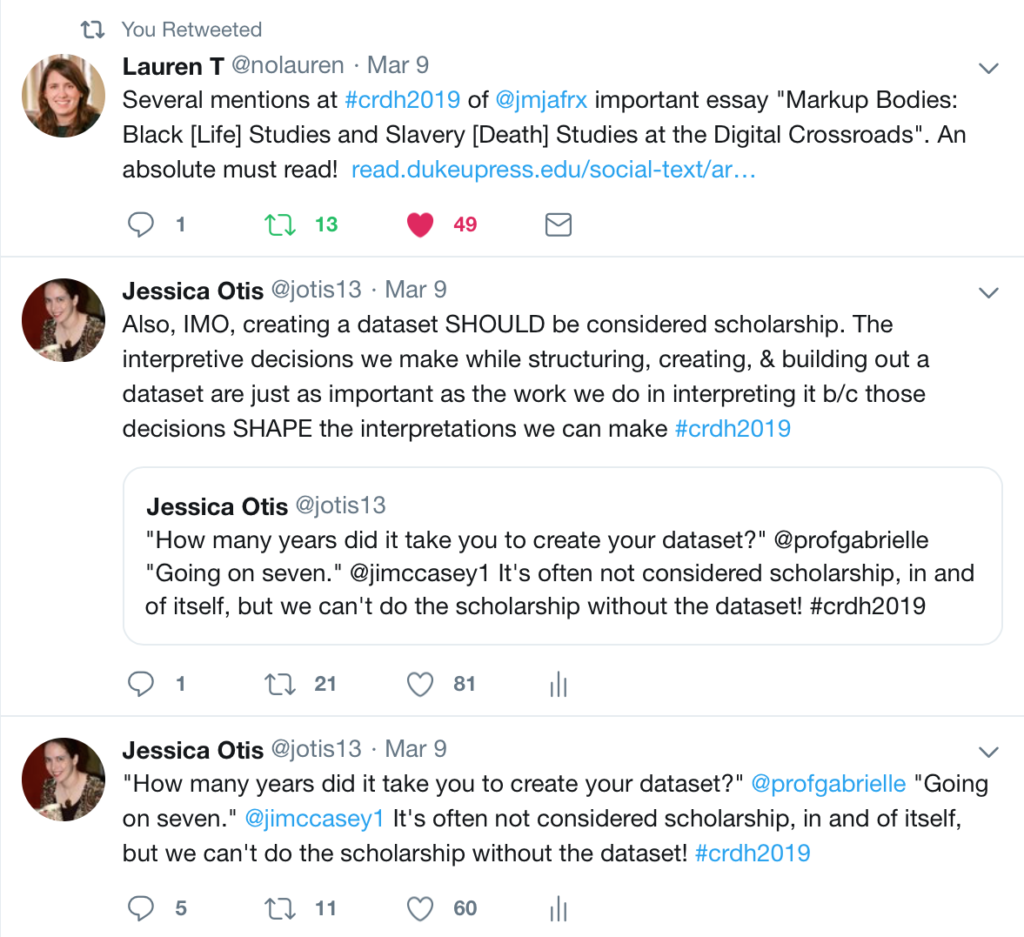

While there were several stand-out tweets that got more traction than others (including the first one pictured at the top of the image, citing Jessica Marie Johnson’s essay, Markup Bodies) one in particular got the most attention and spawned follow-up comment threads (both “on” and “off” hashtag). It was the record of the following brief conversation:

profgabrielle asked jimccasey1, “How many years did it take you to create your dataset?”

jimccasey1 replied, “Going on seven.”

The conversation then continued on (in real life and online) by discussing the fact that creating datasets are not often considered scholarship, despite the interpretation, analysis, and scholarly skill that goes into creating them.

A few scholars chimed in to note that their institutional Promotion and Tenure guidelines had been updated to explicitly include digital scholarship as scholarship, not service. But the conversation largely revolved around the difficulties digital historians face in producing work that doesn’t fit easily into the “monographs, articles, book chapters” model of scholarship that still dominates the majority of the field.

Others noticed that the issues digital historians face in getting their databases recognized a scholarship echoed issues public historians have already been struggling with, particularly getting recognized for the work they do in creating oral history collections. The related issue of crediting the incredible scholarly work of librarians and archivists – which forms the foundation for much historical scholarship – also came up (echoing a few earlier conversations wishing there were more librarians in the room with us!)

Thematically, these conversations tied in strongly with the historical conversations we were having about the need to recover and recognize the vital work of women – especially Black women – in our historical narratives. I want to particularly highlight the Colored Convention Project (CCP_org)’s Teaching Partner Memo of Understanding:

I will assign a connected Black woman such as a wife, daughter, sister, fellow church member, etc., along with every male convention delegate. This is our shared commitment to recovering a convention movement that includes women’s activism and presence—even though it’s largely written out of the minutes themselves.

Building a dataset is hard work, and it’s tempting to focus on the most easily recovered historical figures from the archives. The CCP commits to doing the extra research to figuring out, for example, that “a lady” is actually Sydna E.R. Francis. This is an act of scholarship and we need to figure out better ways to recognizing it as such.

Final Thoughts:

CRDH is a small conference, and a new one, but that enables us to see exactly how widespread its (Twitter) impact is beyond immediate participants in the conference. I haven’t done enough small conference analyses to draw any conclusions about whether or not CRDH is “punching above its weight,” but it’s clear that the conversations we had on Saturday – particularly the ones about recognition and credit, both historically and in terms of our own scholarship – struck a chord with people online and traveled far beyond those rooms in GMU’s Founders Hall. And for anyone who’s now wishing they’d been there in person, hopefully the #crdh2019 tweets will hold you over until the next issue of Current Research in Digital History is published this fall!

Notes on Method/Dataset:

This data was collected via Martin Hawksey’s TAGS. Because the hashtag was created during the conference and the Twitter conversation ended by Monday (yesterday), this is a complete dataset of all tweets with the conference hashtag to date. I’ll be tweeting this blog post with the hashtag, so it will not be a complete dataset of all tweets with the hashtag because that would get circular fast…

For full information on my network creation methods, see this blog post.